Prairie Dog Posse

Without prairie dogs, we would have no prairie. This is the thesis for not only this blog post, but our podcast episode on prairie dogs which goes into even more detail on how important prairie dogs are. Let’s dive a little deeper into prairie dog life, shall we? How are the five species different, just how complicated is their language, and how important are they to their ecosystem?

The Five Species

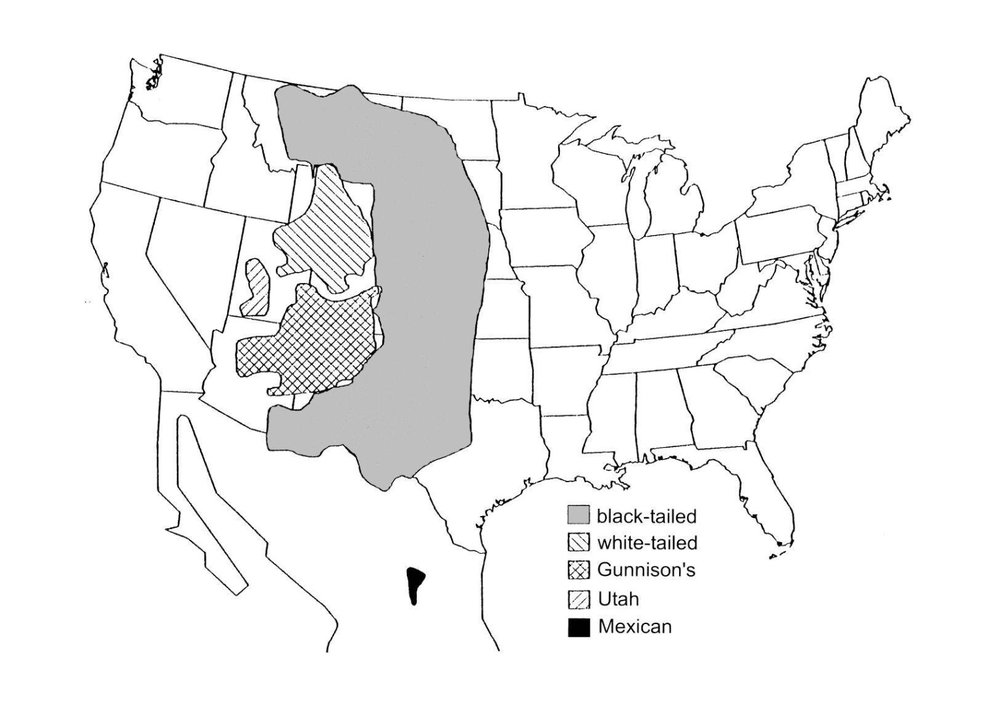

In no particular order, we have the black-tailed, Mexican, white-tailed, Utah, and Gunnison’s prairie dogs scattered throughout North America. They exist in slightly different habitats, but all play a crucial role in that habitat. It is common to lump black-tailed prairie dogs and Mexican prairie dogs into the “black-tailed” group and the other three species into the “white-tailed” group.

Black-tailed Group

Black-tailed prairie dogs are some of the most studied and most numerous both in historic times and in the present day. They once roamed from Texas and North into Canada, and presently reside in small pockets within the Great Plains region of the United States. The largest ever prairie dog town was once in Texas with an estimated 400 million individuals living on over 25,000 square miles (65,000 square kilometers). Mexican prairie dogs (even while often lumped in with the black-tailed species) are very much understudied and exist in much smaller numbers.

There are some protections in place for the Mexican prairie dog (listed as endangered by the Endangered Species Act) while none exist for the black-tailed prairie dog species in the United States. Both species are highly social, and are the only ones to show the “jump-yip” call in which they throw the front half of their bodies in the air and call out to one another. Oftentimes this call is repeated throughout the group in a wave of jump-yips across a colony. It’s as cute as it sounds, trust us.

White-tailed Group

The white-tailed prairie dog group all occur West of the black-tailed prairie dogs and usually in slightly higher elevations where it is colder and drier. The three species are very similar in looks, but occur in slightly different ranges with little to no overlap. All three species will go through a kind of light hibernation known as torpor in which their body slows down and they sleep away much of the winter. The black-tailed species do not show torpor, and can be found above ground foraging throughout the year (though do come out less in winter).

The Utah prairie dog is currently listed as threatened by the Endangered Species Act and the Gunnison’s listed as “special concern” in Colorado which gives them some protection against hunting and habitat loss. Despite these efforts, all three species are in decline.

Prairie Dog Language

If you haven’t yet, spend some time among the prairie dogs if you can. You’ll find that they are constantly moving and constantly communicating through yips, barks, and even tail wagging. A lot of the prairie dog’s language remains a mystery to us, but there is one kind of call which is easy to understand: the alarm call. In a prairie dog colony there is always someone looking out for danger, and if a threat is spotted they will quickly raise the alarm and everyone will dash underground.

Through observations in the field and lab, scientists like Con Slobodchikoff has managed to puzzle out some of these calls. It’s been found that not only do the prairie dogs have calls for different kinds of threats such as humans, coyotes, or hawks, but they can also describe the threat in size, shape, and color. When the prairie dogs were shown unique shapes they wouldn’t see naturally in the wild such as a black triangle they were even able to create new words to describe it. Slobodchikoff describes each yip of a prairie dog as being equivalent to a human sentence. Even if to us the call seems simple, there is a lot of information being passed along to other members of the group. This is why the prairie dog is said to have one of the most complicated languages in the animal world rivaling even that of apes or dolphins.

Learn more about Dr. Con Slobodchikoff’s language work here:

Some places to observe prairie dogs in the wild: Badlands National Park (South Dakota), Kirwin National Wildlife Refuge (North Dakota), Maxwell National Wildlife Refuge (New Mexico), Quivira National Wildlife Refuge (Kansas), Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge (Oklahoma), and many more exist!

Many zoos and nature centers across the globe also have prairie dogs on exhibit, and often have viewing domes you can step into in order to get a closer look. Take time to watch not only how they interact with each other, but all of the different kinds of calls they make. If watching wild prairie dogs, you might have to wait a few minutes after your arrival before they go back to grooming, chasing, and playing with one another.

Keystone Species

Prairie dogs are known as a keystone species meaning that without them, the ecosystem around them would be fundamentally changed. All prairie dogs are hard workers and are constantly digging and clipping down the lawns around the burrows. All this activity actually increases the amount of native plants around prairie dog colonies and over 200 species of animals have been found to have connections to prairie dogs in some way. Usually either by using their burrows as homes, or using the animals themselves as food. There are likely many other connections between prairie dogs and their environment that we are not fully aware of.

Black-footed ferrets are one highly endangered species that absolutely rely on prairie dogs. Not only do they use the burrows for homes, but these nocturnal predators rely on prairie dogs for 90% of their diet. The ferret’s range strongly follows the prairie dogs, and only large groups of rodents can sustain the ferrets. There have been many efforts at released black-footed ferrets into the wild but many sites fail due to the prairie dog populations fluctuating as well as issues with sylvatic plague which is highly contagious in such social animals. Vaccination efforts for both the ferret and prairie dog exist to try to combat plague in colonies.

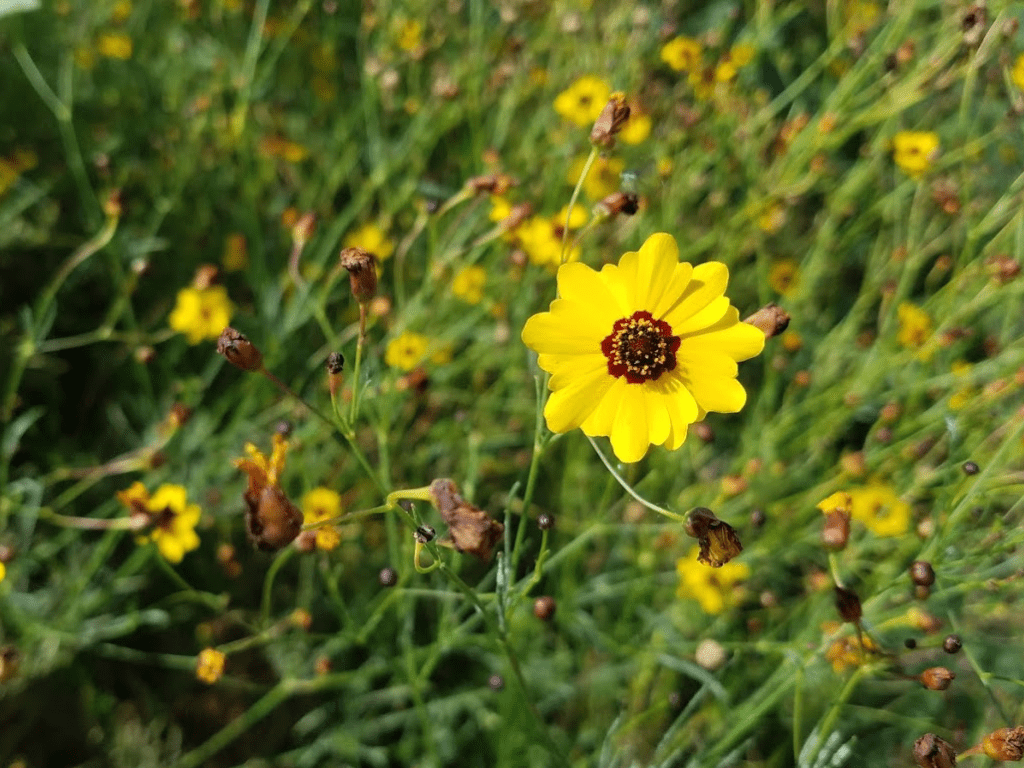

Large grazers such as bison and pronghorn have been found to be drawn to prairie dog towns for grazing. The activity of all the prairie dogs makes for grasses and wildflowers that not only grow very quickly but are also very high in Nitrogen – an element that is useful in digestion and sought after by grazers. When wildfire (which is needed for prairie health) sweeps through the prairie, herds of bison and pronghorn will take cover on top of prairie dogs towns where the fire is less intense due to the short grasses. Even cattle can benefit from prairie dogs and have been found to prefer grazing on colonies.

Ground nesting birds often take advantage of prairie dog colonies as a nesting site. Not only do the birds get a short-grass area that is perfect for their nest, they also get extra pairs of eyes to look for danger as well as an increased abundance of insects for food that are attracted to the colony and the plants there. Burrowing Owls are one famous examples, with the owls often using the prairie dog burrows themselves. With a decline in suitable habitat many owl populations are being given artificial nests to use (as pictured above). Other birds that commonly use prairie dogs colonies as nest sites include: Mountain Plovers, Horned Larks, and Killdeer.

The base of the food web: plants. Prairie dogs have been shown to have a strong connection to not only the diversity of plants that are present, but the plants on colonies tend to be native ones that are adapted to the disturbances like digging and grazing that prairies historically have undergone. You’ll find a wide range of native grasses and wildflowers and a distinct lack of small trees and shrubs which are actively chewed back by the little rodents. With more plants comes more insects, which attracts more birds to eat the bugs, and then more predators like foxes and coyotes. If you ever want to increase the wildlife around your home, planting a garden full of native plants is the way to go!

Only about 2% of the historically high numbers of black-tailed prairie dogs still exist as the prairie they call home shrinks and becomes more and more disconnected. Despite their numbers growing smaller, very little protection exists for these amazing animals. In 2008 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reviewed possible protections for the black-tailed prairie dog but found that despite “conversion of prairie grasslands to croplands, large-scale poisoning, and sylvatic plague… these impacts do not threatened [sic] the long-term persistence of the species.” In 2010 the white-tailed prairie dog was also petitioned and declined for a listing of threated by Fish and Wildlife. There are groups still out there fighting for the prairie dog, and we hope that you fight for them too. Check out the links below to learn more about prairie dogs and the conservation work being done to save them.

Prairie Dog Conservation Organizations

How can you help?

One of the biggest threats to prairie dogs is simply misinformation. They are classified as pests in most of their range, and few people realize their true worth. Sharing what you’ve learned about prairie dogs to others is a huge step forward, as well as writing to local, state, and federal lawmakers to bring attention to the plight of the prairie dog. Avoid pesticide and herbicide use as much as possible, and if you have land consider opening it up to prairie dogs for a trial run. You may just find that your land blossoms under their care. If you’d like to learn more about the prairie ecosystem these guys live in, you may do so right here on our website.

Sources/Further Reading:

- Slobodchikoff, C. N., Perla, B. S., Verdolin, J. L. (2009). Prairie Dogs. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lipinski, A. R. (2014, May). Plant and Bird Community Dynamics in Mixed-Grass Prairie Grazed by Native and Domestic Herbivores, Rangeland Ecology & Management.

- Winter, Stephen L., Plant and Breeding Bird Communities of Black-tailed Prairie Dog Colonies and Non-colonized Areas in Southwest Kansas and Southeast Colorado (1999). Dissertations & Theses in Natural Resources. 95

- Beals, Stower; et al. (01 May 2014) The effects of black‐tailed prairie dogs on plant communities within a complex urban landscape: An ecological surprise?

- William H. Keeley, Marc J. Bechard, Nesting Behavior, Provisioning Rates, and Parental Roles of Ferruginous Hawks in New Mexico, Journal of Raptor Research, 10.3356/JRR-16-85.1, 51, 4, (397-408), (2017).

- Johnson, D.H., D.C. Gillis, M.A. Gregg, J.L.Rebholz, J.L. Lincer, and J.R. Belthoff. 2010. Users guide to installation of artificial burrows for Burrowing Owls. Tree Top Inc., Selah, Washington. 34 pp.

- Merriam, C.H. 1901. The prairie dog of the Great Plains. USDA Yearbook of Agriculture. pp. 257-270.

Did you spot an error or have questions about this blog post? Just want to rave about prairie dogs? Email Nicole Brown at: nicole@grasslandgroupies.org