Camels are Grasslanders

I’m here today to tell you that the desert-y camel we all know and love is actually the exception, because grassland camels are the rule. Grasslands birthed the camel, nurtured its adaptations to the harsh arid landscape, and sent them off to colonize arid steppes, the arctic, and even the desert.

Only one camel is wild.

Of the three species that exist today, only one remains wild. And it’s not the wild ancestor of its domesticated counterpart.

Defining camel traits:

Flat feet with splayed toes and big flat toe pads, a pacing gait (which gives them an awkward rock as they walk), canines in the upper and lower jaws, and some crazy adaptations to surviving harsh environments, including arid grasslands and deserts.

Their humps store fat while they travel long distances, and their unique oblong blood cells store water. Together with incredible olfactory systems, they find browse, water, and even other camels by the smells carried over open landscapes.

Camels have been domesticated for about 5,000 years, and their relationship to human history, trade, culture, and even pure human survival runs deep.

Dromedary Camel (Domesticated)

Camelus dromedarius

The camel that usually comes first to mind, the Dromedary is also undeniably a desert-dwelling animal. This one-humped camel was domesticated in Africa and has long, gangly legs.

In winter it grows a long, shaggy coat which it loses in the heat of summer. It’s completely domesticated, but it’s established feral populations in Australia.

Also called Arabian Camels.

Bactrian Camel (Domesticated)

Camelus bactrianus

Bactrian camels, domesticated in central Asia, are native to the Eurasian steppes. These two-humped camels have short, stocky legs, and they tend to be bigger than Dromedaries.

They’re also capable of surviving harsh conditions and traveling long-distances, making them useful to humans since they first encountered each other.

Some call them Mongolian Camels, but you’ll usually see them as “Bactrian,” referencing an ancient nation around Afghanistan that doesn’t exist today.

Wild Bactrian Camel

Camelus ferus

Wild Bactrians look superficially similar to the domesticated Bactrians. But they’re not the ancestors of the domestic ones; their species diverged from the true ancestor of the domestic Bactrians 1.1 million years ago.

They are the only mammal that can drink water saltier than the ocean, and not even the other Bactrian camel can.

Conservation for this critically endangered, incredibly rare and unique animal is hugely important. Xinjiang Lop Nur Wild Camel National Nature Reserve is one protected place these camels are found.

Wild Camel Protection Foundation exists solely to protect this wild camel and its fragile habitats in China and Mongolia. They’re currently raising funds for a new breeding centre, so pitch in if you can help.

Grasslands, you say?

Why yes.

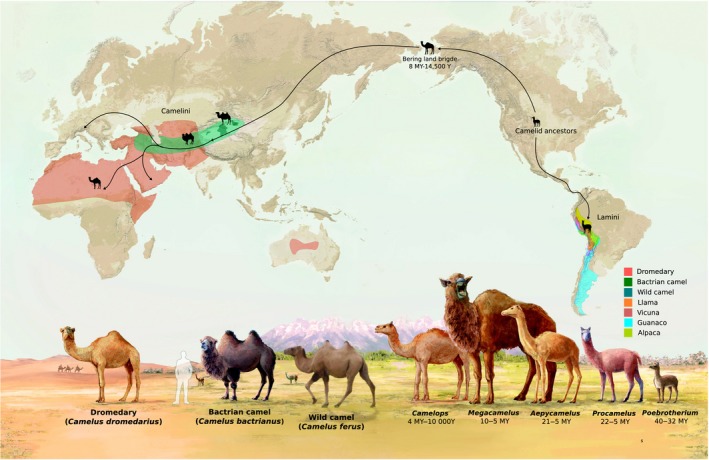

The wild camel’s range includes grassland and desert in Mongolia and China today. But the global history of camelids? That story begins in North America.

And we have two other camelids alive on the planet today, also domesticated; llamas and alpacas. Their wild counterparts, guanacos and vicugnas, still live in South American grasslands today.

North America: the birthplace of camels

While the first deer-like ungulate to have some camel features, Protylopus, was born in a North American rainforest, camels began to take form in the wooded grasslands and shortgrass prairies of the North American Eocene. Poebrotherium, which included some gazelle-like camels, had no hump or toe pads. But Eocene camels were just the beginning.

During the Miocene, when savannas and grasslands exploded, so did camels. PBS Eons (below) does a great job exploring this camelid explosion, which included such amazing creatures as Aepycamelus, a giraffe-like camel that used its long camel stride to cross open grassland in search of trees on the savannahs.

Globetrotting camels

As continents shifted and new bridges occurred in Alaska and Mexico, camels escaped North America and spread to other parts of the globe.

Modern camels descended from a two-humped camel, which diverged into several species as populations explored into Asia and Africa. The species that was domesticated into the modern Arabian (Dromedary) camel evolved a single hump later on.

In the Americas, a llama-like camel spread into South America, eventually speciating into extinct and extant species that we recognize today: wild guanacos and vicugnas, and domesticated llamas and alpacas.

Interesting that most of the camelids that exist today are all domesticated in some form.

Why don't we have camels anymore?!

It probably has to do with multiple factors, including humans and diet.

Camels are primarily browsers, meaning (like deer for example) they feed mostly on shrubs and other woody browse. As North American grasslands became prairies, or large expanses of treeless plains, camels couldn’t thrive as well as they could on the more shrubby steppes and savannas from the past.

We also know that the few camels that stuck around in North America when humans entered the scene were often hunted, from butchered bones of the Pleistocene Western Camel (Camelops hesternus) that have been found.

C. hesternus was also found in the Yukon in 2008, demonstrating just how many harsh conditions camels could thrive in, besides grasslands and desert. The woody browse killed off in that region as temperatures dove also wiped this camel from the Yukon.

Camels are not ruminants.

The process of rumination (which kangaroos, hippos, and other animals like camels can do in part) and the taxonomic classification of ruminant (cows, sheep, and other livestock) are not the same thing. Unfortunately, camels are often labeled as ruminants, which has real-world consequences when, for example, lawmakers misunderstand these labels.

In a 2008 paper by Murray Fowler, DVM, he says unequivocally that “Camelids are not ruminants taxonomically, physiologically, or behaviorally.”

When it comes to livestock diseases in particular, this is important. Because camels are not ruminants, they are not susceptible to disease in the same way as actual ruminants. Fowler’s paper details with tables upon tables of data how camelid and ruminant disease transmission overlaps (or doesn’t).

Sources/Further Reading:

- Fowler, M. E. (2008). Camelids are not ruminants. Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine, 375-385. doi:10.1016/b978-141604047-7.50049-x

- Burger, P. A., Ciani, E., & Faye, B. (2019). Old world camels in a modern world – a balancing act between conservation and genetic improvement. Animal Genetics, 50(6), 598-612. doi:10.1111/age.12858

- Cui, P., R. Ji, F. Ding, D. Qi, H. Gao, H. Meng, J. Yu, S. Hu, H. Zhang. 2007. A complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the wild two-humped camel (Camelus bactrianus ferus): an evolutionary history of camelidae. BMC Genomics, 8/241

Did you spot an error or have questions about this post? Email Rachel Roth.