Takhi

From humble 14-hooved beginnings to beasts of war we ride into battle, horses have developed into beautiful animals worthy of respect. Let’s take a look at the evolutionary and cultural history of horses, as well as a deep dive on the last remaining wild horse in the world.

Horses are weird

The evolutionary history of horses actually closely mirrors that of camels. Both began in North America with a steady spread to South America and then to Europe over the Bering land bridge.

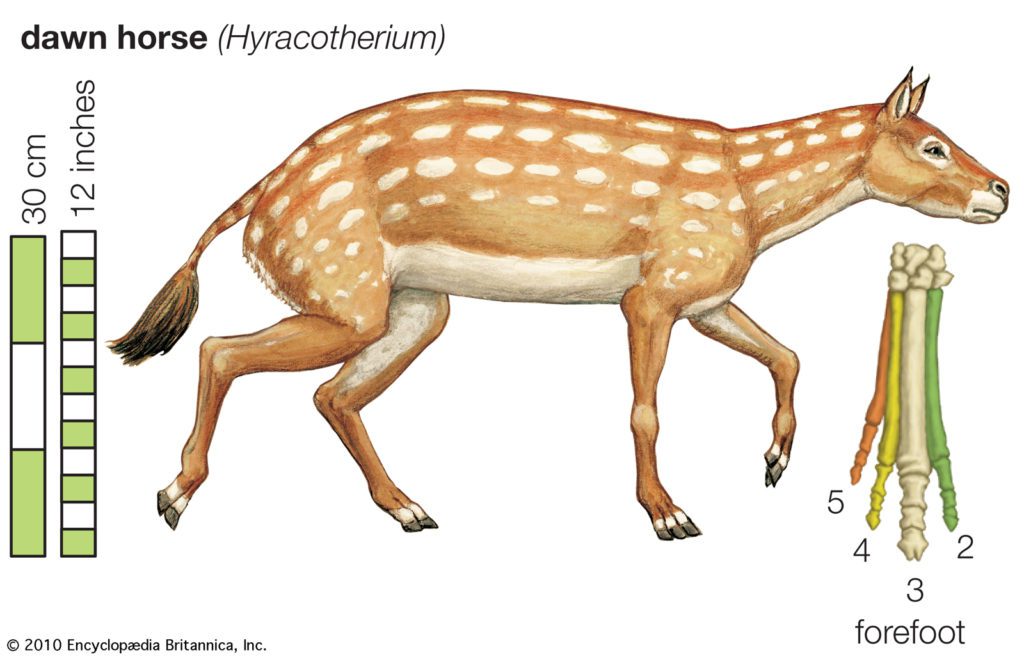

The very first animal we can definitively call a horse was known as Eohippus or the dawn horse. This strange little horse stood only about 50 centimeters (20 inches) tall, had padded feet, and had four hooves on each front foot with three on their back.

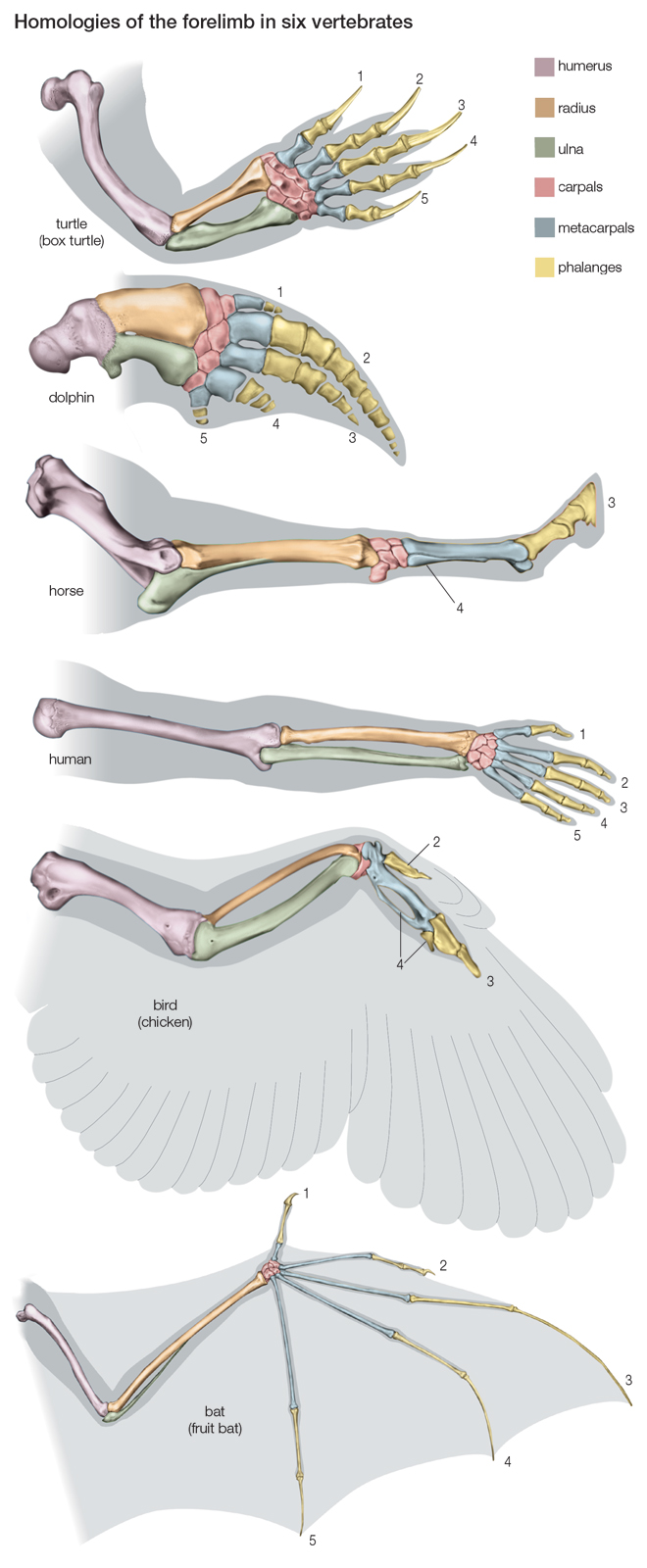

Modern horses are equally strange though admittedly with fewer hooves. They have evolved to have fused lower leg bones for strength, as well as elongated middle digits to stand on. Yes. Horses stand on just one toe (their hoof) and are constantly giving you the bird. Also, that joint about halfway up their leg? That’s their wrist, not their knee.

Horse Domestication

There is some controversy over where and when horses were originally domesticated. Modern research points to many smaller domestication events rather than one large one. People would take horses in their care and breed them to wild horses to increase genetic diversity or add in desired traits. Over time, the horse was domesticated and able to be used to benefit humans. Currently it is believed horse domestication occurred about 6,000 years ago in the Western Eurasian Steppe in an area covering Ukraine to Kazakhstan.

One really interesting way that anthropologists have helped narrow down the time period of horse domestication is by looking at the teeth of ancient horses. Metal mouthpieces were common in bridles to help control the horses and these bits left distinctive marks on the horse’s teeth. There have even been ceramic pots found with evidence of horse milk in them.

Horses of Botai

And then, there’s the horses of Botai which led to even more controversy. In our Two Truths and a Lie episode we mentioned that the Przewalski’s horse (P-horse) might not actually be the last wild horse. This discovery in 2018 led to this controversial take as many, many horse bones were found in the city of Botai. Those bones did not belong to domesticated horses however, but rather the P-horse. After taking another look at the evidence however, it is now thought that the Botai horses were actually a failed domestication event. This leaves the P-horse with the last wild horse species crown. This is an important distinction since other horses such as the American mustang or Australian brumby are escaped domestics which have turned into feral populations.

Horses as a Way of Life

The trading of horses (or using horses to carry goods) was extremely lucrative and quickly became a way for people to create a new kind of living. Once horses were domesticated by people they became a huge part of human culture. They have been used as a source of meat or dairy, a way to travel vast distances, a way to carry goods or pull plows, and even in war. The nomadic lifestyle that so suits the animals in grasslands now became much easier for people to emulate and follow herds of wild animals or avoid extreme weather. Especially for the people of the Steppe both historically and in modern times the horse is incredibly important. I would love to visit Mongolia and see people hunting with eagles from horseback then relax by the fire with a nice bottle of kumis (fermented mare’s milk).

It’s extremely difficult to learn more about early nomadic people on the Steppe, especially as horses were domesticated and people had to move more often in order to feed their herds. Very few permanent structures exist, and much of our knowledge about these nomads come from accounts of nearby civilizations which relied more on farming and a sedentary lifestyle.

Empires Built on Horseback

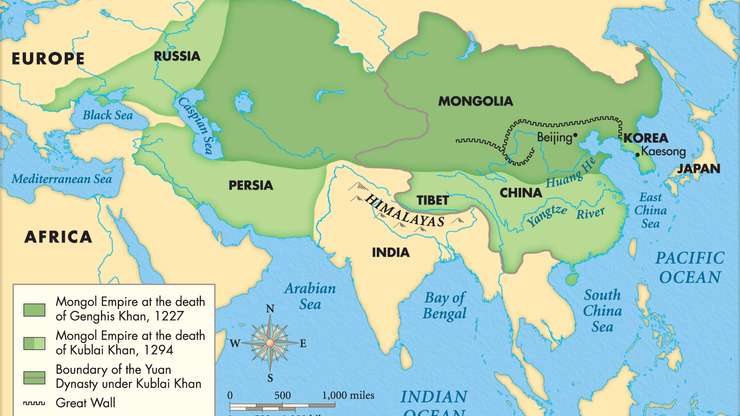

While not all nomadic tribes in the Steppe were war-faring, two better known examples were: the Hun and Mongol Empires. They used horses to their advantage to take over much of the Steppe and even much of Europe and Asia outside of the Steppe. Their powerful horse armies were nearly unstoppable and it was some time before cities could fortify themselves and create weapons to destroy the horse-led armies. After the fall of the Mongol empire (which covered a whopping 22% of the world) many smaller nomadic tribes were displaced by the now stronger civilizations on the outskirts of the steppe but many exist still today. The Silk Road trading route was also largely built on the back of horses both as a trading commodity and as a way of carry goods and wagons.

The Last Wild Horse

The Mongolian word for the P-horse is takhi, meaning “wild” or “worth of worship”. These horses truly are amazing animals. The International Takhi Group is by far one of the most comprehensive resources on information about the takhi. Listed as Endangered by the IUCN, the takhi is a broad-faced, rich brown colored horse with accents of creamy-white on its belly, muzzle, and around its eyes. As of October 2020, there are 320 takhi in the wild in the Great Gobi B (part of their native habitat), 56 being foals.

While 300 horses doesn’t sound like a lot, it’s actually quite an impressive feat of conservation considering the takhi was once extinct in the wild. Around 1800 Russian explorer Nikolai Przewalski had a takhi skull and pelt gifted to him by the Mongolian people. He brought the biofacts back to the Western world where the animal was promptly named after him. Ecstatic at the new find, the turn of the century saw collectors taking takhi from the wild for mounts, zoos, and private collections. In the 1960s the last takhi was seen in the wild in the Great Gobi B nature preserve.

The population hit an all-time low in the 1940s when only 13 breeding individuals were left in the world. Luckily, conservationists realized what was happening to the last wild horse and breeding to save the species began. In the early 2000s the takhi was released back into the Great Gobi B, just a few miles from where the last wild takhi was seen. People traveled for days to watch the release of the horses into their ancestral land. Today, there are about 2,500 takhi in the world in captivity and in the wild. Again, up from just 13 in the 1940s.

Video of the takhi’s return to Mongolia.

Conservation with a Twist

Perhaps part of the reason that the takhi conservation has been so largely successful is due to the unique ways that Mongolia has opted to do their conservation work. The Great Gobi B itself is a very unique type of park called a Biosphere Reserve. These types of land set aside for conservation are not without human habitation and in fact encourage the sustainable use of land in and around the reserve. This avoids an either-or situation and gives the people living there a sort of agency over their land which in many cases has been lived on for generations. Worldwide, there are about 257 million people living on 701 biosphere reserves in 129 countries. This cooperation with local people rather than excluding them is very effective, as they can still raise livestock, help run tourism, and generally make a living on the same land being used to protect endangered species.

Another great example of collaborative conservation is a paper published in 2012 which counted various species of animals on the Great Gobi B with the help of locals. This huge undertaking included 50 sample points which were all counted simultaneously. In the article they mention that incorporating local people in this way “created vested interest in conservation by the people who are most influential in, and most affect by, the outcomes”.

Great Gobi 6

Another great tactic is the lumping of megafauna into what is known as the Great Gobi 6. All of these species are in need of conservation, and by creating a united front it makes finding support for conservation projects that much easier. A genius approach. The six species represented are: the takhi, wild Bactrian camel, Gobi bear, Khulan, saiga antelope, and the goitered gazelle.

How to Help:

While takhi numbers are on a steady increase, a local wild population of at least 1000 is recommended by IUCN to create a sustainable species. Helping is as easy as learning more about the takhi and spreading the word! A donation to the International Takhi Group or similar organizations are another good option. For general conservation efforts, encourage your local governments to adopt Biosphere Reserve tactics that include local human populations, and participate in citizen science when given the chance. Good options for citizen science include eBird, iNaturalist, FrogWatch, and websites like Zooniverse.

Sources/Further Reading:

Origin of horse domestication. Britannica Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 07, 2021.

Biosphere reserves. (2020, October 30). Retrieved April 07, 2021.

Kaczensky, P., Burnik Šturm, M., Sablin, M. V., Voigt, C. C., Smith, S., Ganbaatar, O., et al. (2017). Stable isotopes Reveal diet shift FROM PRE-EXTINCTION TO Reintroduced Przewalski’s horses. Scientific Reports, 7(1). doi:10.1038/s41598-017-05329-6

Ransom, J. I., Kaczensky, P., Lubow, B. C., Ganbaatar, O., & Altansukh, N. (2012). A collaborative approach for estimating terrestrial wildlife abundance. Biological Conservation, 153, 219-226. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.05.006

William Taylor Assistant Professor and Curator of Archaeology. (2020, March 02). Humans domesticated horses – new tech could help archaeologists figure out where and when. Retrieved April 07, 2021.

Did you spot an error or have questions about this post? Email Nicole Brown.